Art & Design

How Art and Design Gave the Revolution Its Icons

by Iain Akerman

January 11, 2020

.jpg) Advertisement

Advertisement

“It’s not the traditional designer that is most active,” says Areej Mahmoud, a director, visual artist and creative director based in Beirut. “Anyone with a smart phone and a photo or video editing app is a revolution designer. Their wit and humour is raw and honest, naming and shaming unapologetically, saying what they think with poetry and humour and soul and love and passion. They’ve made us laugh and cry and rush down to the streets with our flags. They don’t care for credit. They’re just in service of the revolution.”

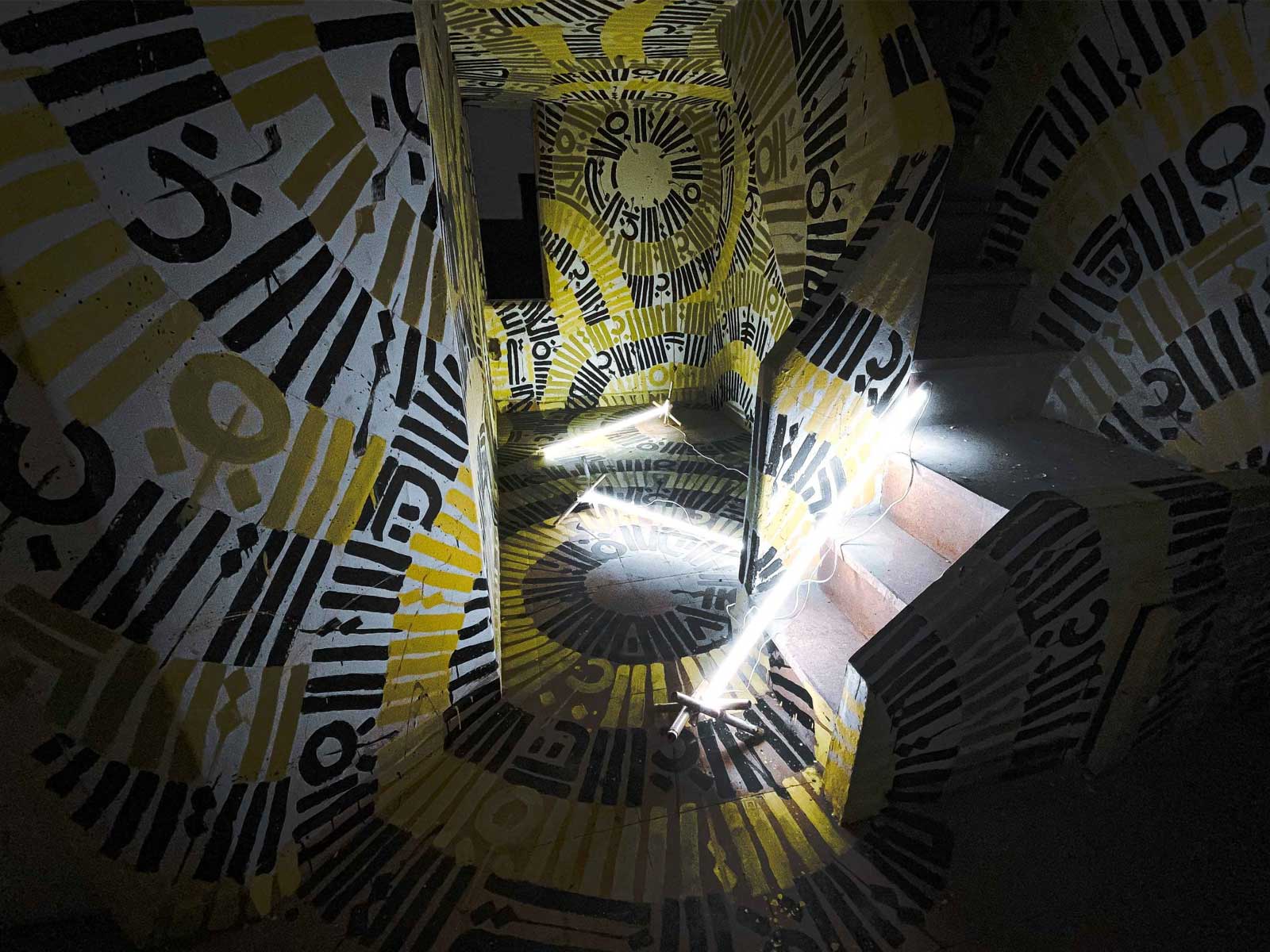

Since the protests began on 17 October, art and design have played a key role in not only defining the revolution, but in expressing its emotions and beliefs. From the raised clenched fist in Martyrs’ Square, to the ubiquitous use of graffiti, the lovingly hand-drawn illustrations, and the plethora of digital artwork, the revolution has been defined as much by its iconography as it has by its chants and digital communication.

“Anyone with a smart phone and a photo or video editing app is a revolution designer.”--Areej Mahmoud

Of that iconography, the most remarkable is of women, believes Mahmoud, with the first female icon of the revolution appearing almost immediately. Soon after Malak Alaywe Herz was famously captured (on film) kicking a bodyguard of the politician Akram Chehayeb, the London-based graphic and motion designer Rami Kanso turned the image into the revolution’s first piece of viral artwork.

“As an artist in the diaspora who couldn’t be physically present on the streets, I felt I should participate in the way that I could and through the media that I love – art and design,” says Kanso. “To me, this image represents the person vs the gunman, the citizen vs the political convoy, the woman vs the oppressor.”

“To me, this image represents the person vs the gunman, the citizen vs the political convoy, the woman vs the oppressor.”—Rami Kanso

The revolution has, believes Kanso, turned designers and illustrators into “grassroots artists”. Artists who are creating work according to their own style and inspiration, are free of the clean structure of marketing, and are talking to their audience in their own voice. “This has manifested in a rich and diverse art production, which in turn has created a decentralised visual language for the revolution, which I find great and beautiful,” he says.

“Lebanon has always faced political and social uprisings and resistance, though most of these moments were controlled and guided by political parties,” he adds. “Commonly, the visual artwork was always guided by political parties’ marketing machines. The spontaneity of this specific movement, which is by its very nature anti-establishment, has given artists a wide range of space to express without having a party’s vision. Breaking free from them gave the artist the importance of translating the emotions of the streets into a visual design.”

He’s far from alone. Hundreds of artists, illustrators and designers are producing widely divergent imagery. There’s Nour Flayhan, with her distinctive portraits of activists, Dana Osman, who redesigned the Lebanese currency with images from the revolution and the illustrators Sasha Haddad, Michelle Khalil, Nour Ayoub and Raphaelle Macaron. There are type designers and calligraphers, too, including Kristyan Sarkis and Joseph Kai, both of whom have produced strong iconography based on Arabic calligraphy.

Much of their output is being collected, or curated, by the Art of Thawra, an Instagram account created by Midnight Cravings’ Paola Mounla. Launched on 21 October, it had already amassed 1,511 posts and 15,600 followers at the time of going to press.

“These pieces will forever exist, be used in schools and in books and go down in history as part of the Lebanon 2019 revolution.”—Paola Mounla

“We’re documenting artistic history,” says Mounla. “With this magnitude and amount of content, it must be a first for the country. These pieces will forever exist, be used in schools and in books and go down in history as part of the Lebanon 2019 revolution. They capture key moments and events, forever immortalised in artwork. They will tell a story by the people, the artists of the nation. And that is important because this is how a country learns from its past. This is how the world learns from the past of a country. This is how we evolve and create a better future. By documenting it and remembering it.”

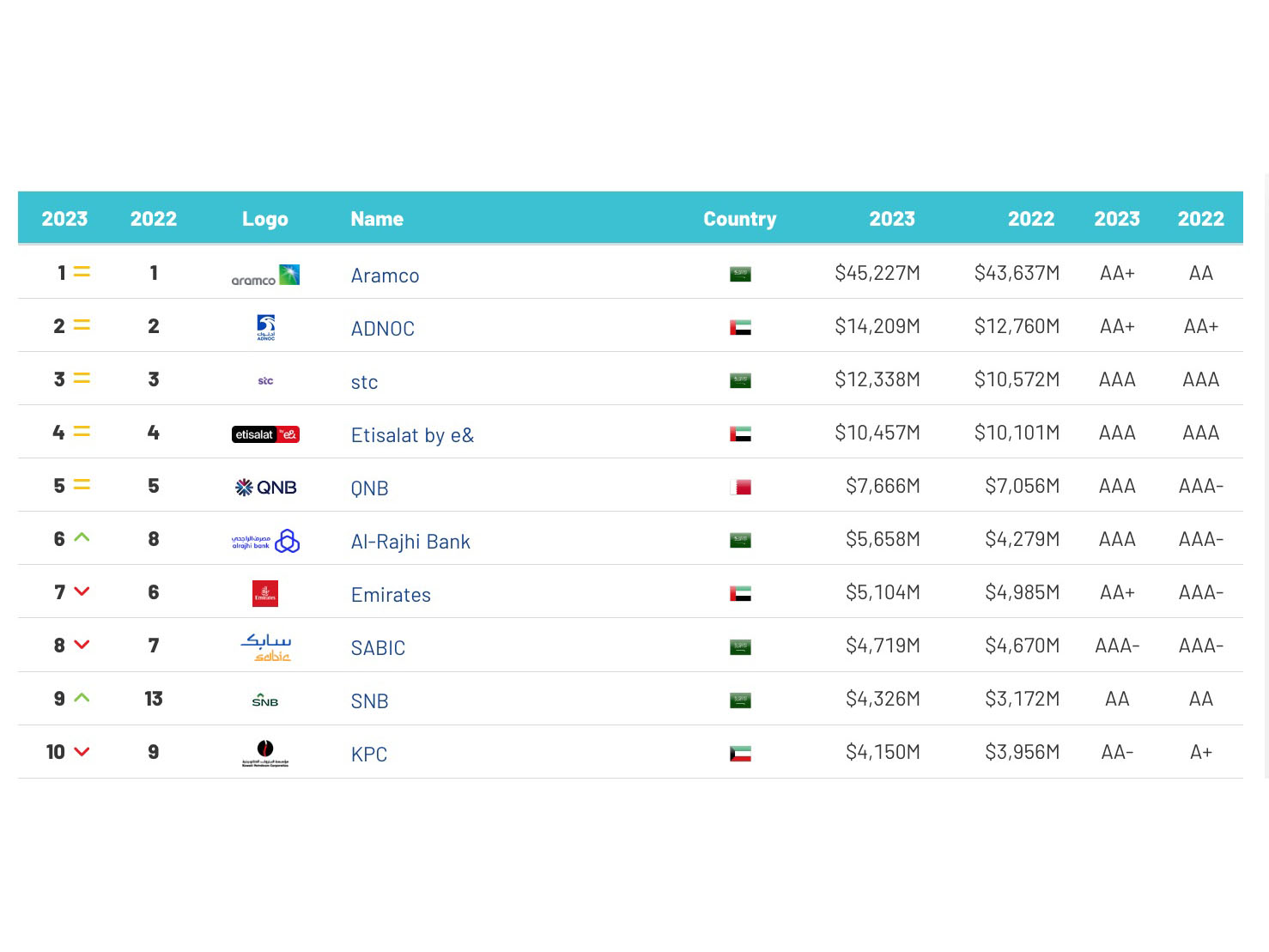

Importantly, the imagery being produced is not just about self-expression and solidarity. It has also embraced infographics, with designers using the medium to “present to the masses (in facts and figures) the ways the political regime has corrupted our economy”, says Kanso. “The simplification of information for the audience will have an impact in the long run in understanding how complicated corruption works.”

Kanso’s talk of the long term is important. How is it influencing the outcome of the revolution? Can it help bring about lasting change? Is it all in vain?

“Art is freedom of expression, art is an intellectual and peaceful way for people to express themselves and get their ideas and emotions across,” says Mounla. “Art is a means to let it out creatively and reduces violence. I believe that is the role art is playing in this revolution. A catalyst of freedom and peace. An outlet.”

“Activists can bring change. But change does not come only through design,” says Mahmoud. “Real change can begin to take place when able and qualified people take over unions and syndicates, municipalities, the parliament, when laws begin to change, and the judiciary system becomes independent of the corrupt political class. Until then, designers and artists have a responsibility to serve the revolution, and maintain the momentum.”

.jpg)