Industry Talk

Nayla Tueni: ‘We have to be the voice of the people’

by Iain Akerman

January 3, 2020

.jpg) Advertisement

Advertisement

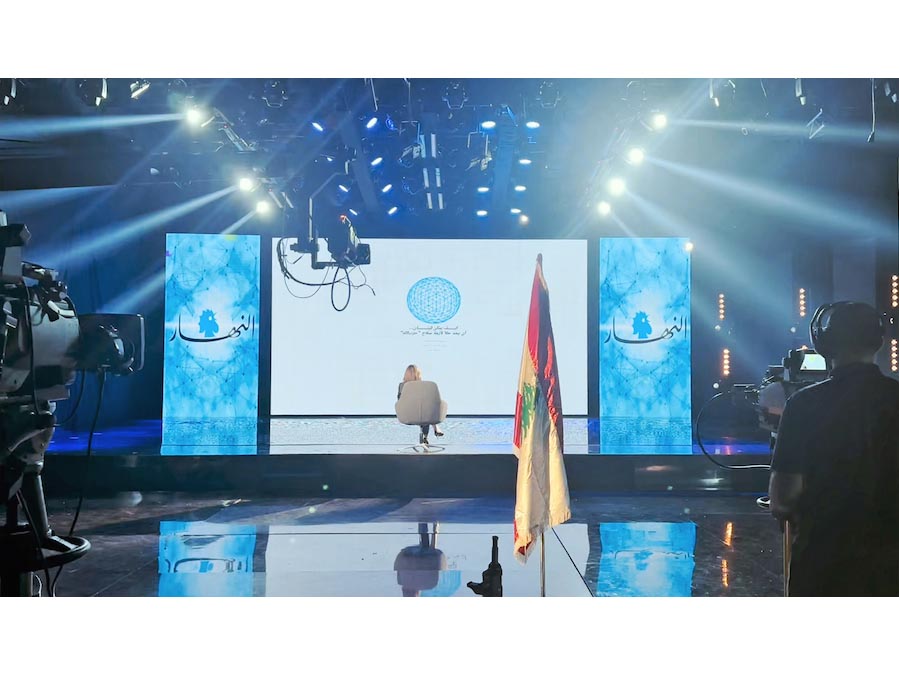

Nayla Tueni, the editor-in-chief of An-Nahar, is sitting quietly in the office of her father, Gebran Tueni. “You know, in 2005, when my father made his speech downstairs [in Martyrs’ Square], he said that the Lebanese had to be unified as Muslims and Christians to defend our Lebanon,” she says. “And I have been surprised and emotional to hear people saying it again and again once more. This tells you a lot about what we, as journalists and as media, can do.”

These are both exciting and troubling times for An-Nahar. Like all newspapers, it is struggling with the continued loss of its sources of income and is battling to remain relevant in a world dominated by Google and Facebook. Yet it also finds itself covering two of the country’s biggest news stories – Lebanon’s potential economic collapse and a popular uprising that has swept across much of the country. The latter, at least, is what newspapers thrive on.

“All the journalists have been in the streets covering the voice of the people, their anger, what’s happening, what they want,” says Tueni. “It has been tough. All the team have been working 12 to 18 hours a day and we are on WhatsApp groups 24 hours sending photos and voice messages. We even have a lady whose job it is to fight fake news. It really was the time of fake news. Every day we have tonnes of fact-checking work to do. You have a lot of voices, messages, images. Even one of the [rival] newspapers, unfortunately, used a fake photo from a drone on its front page. This is one of our missions. To really fight fake news and to really work on fact-checking.”

All of this is happening at a time of protracted financial crisis for the newspaper industry. Even if newspapers live or die on era-defining events, especially ones that are continually evolving, the constant need for printed editions, live news, and social media updates requires a ready supply of money and staff. Something An-Nahar doesn’t have. Cuts, or the threat of cuts, have been a regular part of An-Nahar’s existence since the assassination of Tueni’s father, the paper’s former editor and publisher, in 2005. Job losses and recriminations hit the paper in 2016 and even its ‘Blank Edition’, which became the first campaign from the region to win a grand prix at Cannes earlier this year, was partially motivated by the newspaper’s financial plight.

"We drastically cut costs three years ago and we’re still struggling,” admits Tueni, a former deputy under the March 14 Alliance. “But it [has been] better with the [introduction of] premium online subscriptions. But it’s a slow process. It will take time and we don’t have much time. We are trying to find solutions and we’re trying to work on projects that advertisers can become involved in, but it will be very difficult for us. Who’s going to run an ad now?”

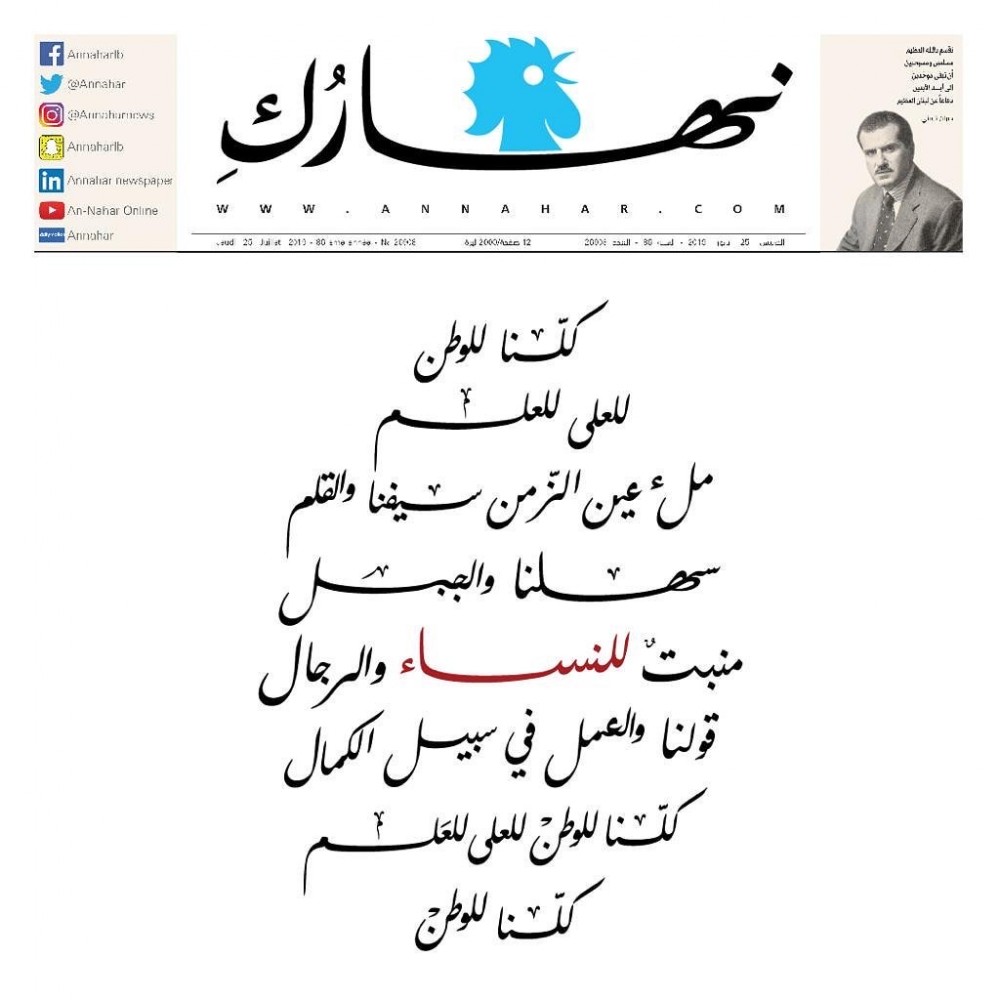

Within such an environment the newspaper’s objectivity and impartiality is key, says Tueni. So, too, is its embrace on causes. On 31 October, for instance, a special edition dedicated to the women of the revolution tweaked the national anthem to include the word ‘women’ in a sentence that only refers to men. It also rebranded its name to Naharouki, which translates to ‘Your Day’ when said to a woman.

“An Nahar is always with the people,” says Tueni. “We cover everyone, but the most important thing is to be the voice of the people… I believe that we have a big role to play. I believe there is a future for newspapers. But the most important thing is to change with the generations. To change with the young and with technology. You have to be updating yourself, working on yourself, challenging yourself every day. Even if we have a big crisis, we always have to be innovative and find new ideas.”

An-Nahar is no longer a singular medium. It is in print and online, goes live via Facebook, has its own web TV, and is present on all social media platforms. Its circulation figures are “stable”, says Tueni, averaging 20,000 to 25,000 printed copies a day – a figure that nevertheless represents a significant drop on the 45,000 claimed in 2012. It has attracted “8,000 to 9,000 premium online subscribers”, while its website had 10.67 million page views in November across the Levant and the GCC. Its unique browsers for the same period stood at 2.4 million. All of which is supported by a strong social media following – 1.8 million on Facebook, 759,000 on Twitter, and 103,000 on Instagram.

“I believe in what we’re doing and that it’s a mission,” says Tueni. “When the protests started you felt you didn’t want to leave the office. You wanted to go down to the streets, not to protest, but to see and to feel the people and what they want. To hear them, to listen, to see what they’re really doing.

“For me, it’s a huge responsibility, but I believe in it. And I’ve been trying since 2005 to do whatever I can to keep the newspaper and its legacy alive, not because it’s a family business, but because it’s a mission. My father died for the freedom of the press and to say what he had to say in a loud voice. I want to keep that alive.”

.jpg)