News - Advertising

Advertising as a Positive Force for Good

by Iain Akerman

August 12, 2017

.jpg) Advertisement

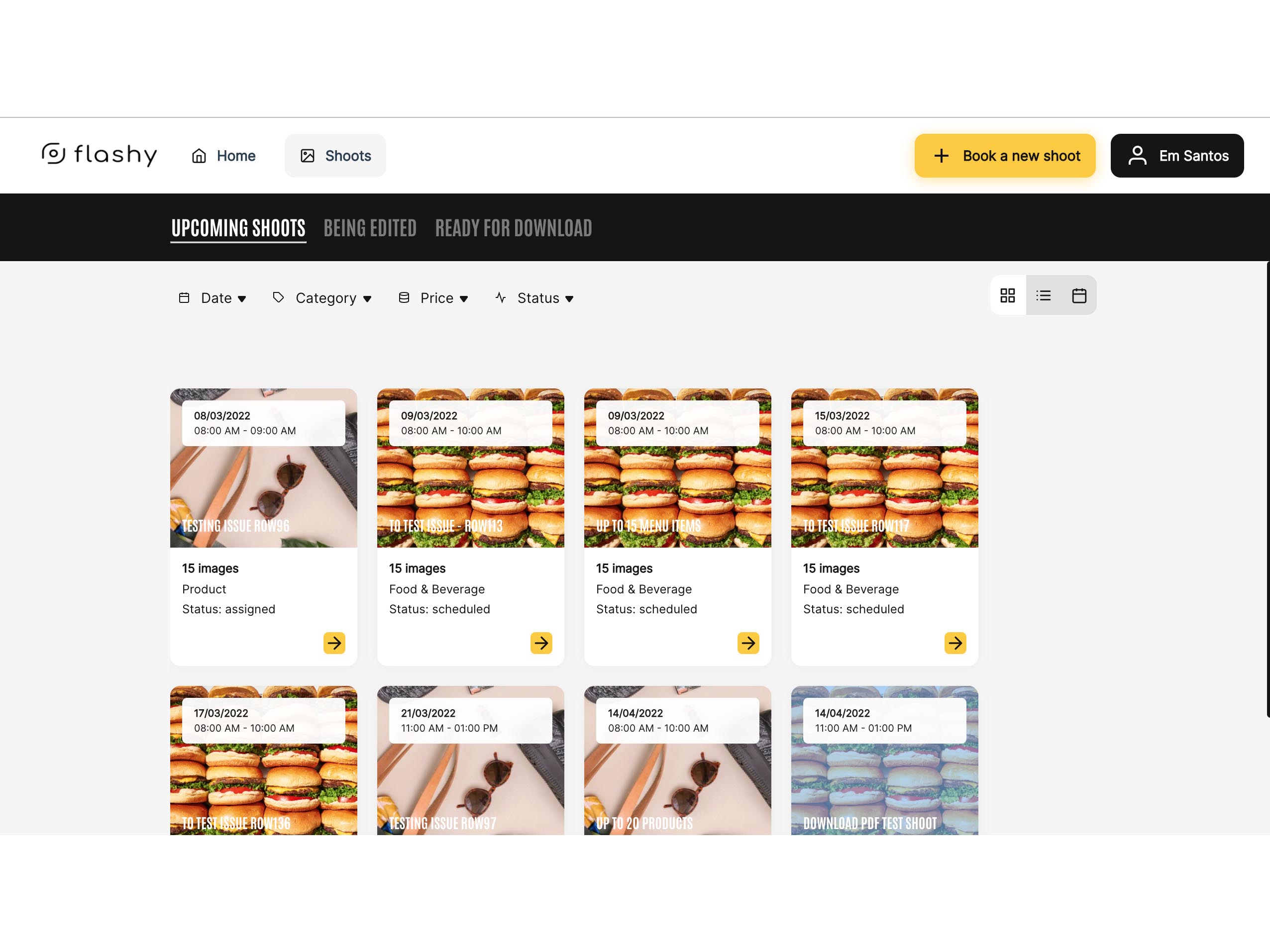

AdvertisementCan advertising be a force for good? An increasing number of brands and agencies seem to believe so.

Improving profitability while bettering society is flavour of the month, with consumers not only expecting brands to reflect their ideas and principals, but to be socially and environmentally responsible in an era of unprecedented change.

This concept is nothing new of course, but the various monikers available to help describe this swing towards benevolence has increased. ‘Advertising for social good’, ‘cause marketing’, even ‘goodvertising’. The latter – what Paul Barrass, chief creative officer at Dubai-based Face to Face, describes as “a toe-curling portmanteau” – was first coined by Thomas Kolster, a Danish strategist. It is essentially the desire to create advertising as a source of good.

“Nowadays, consumers expect brands to make a difference in the community and make a positive contribution to society besides selling goods and services, and advertisers are responding to that shift with an increased adoption of social branding,” explains Nadim Khoury, chief executive at Grey MENA.

“For a social-cause ad to be effective, it has to be genuine and has to sit at the heart of a popular culture.”--Nadim Khoury

There are, however, many facets to the topic. Firstly, what can be described as ‘meaningful marketing’. That is, campaigns that confront social issues as part of a company’s brand marketing. Always’ #LikeAGirl, which challenged gender stereotyping, or Dove’s ‘Real Beauty’, which challenged perceptions of beauty, are examples.

Then there are agencies that work for charitable or other organisations to create work for the greater good. Think the road safety campaign ‘Meet Graham’, a Cannes grand prix winner for Clemenger BBDO Melbourne and Australia’s Transport Accident Commission, which imagined what humans would look like if our bodies evolved to withstand car-crashes. Some of this work is done pro bono.

Regionally, Leo Burnett Beirut has done a lot, most recently with ‘Undress522’ for women’s rights NGO Abaad, which tackled an archaic article of the Lebanese penal code that states that if rapists marry their victims they will be exonerated. Article 522 was abolished by the parliamentary judicial committee and now only needs to be ratified by parliament.

“More than a decade ago, Leo Burnett Beirut put its conviction and its ‘HumanKind’ philosophy into action,” explains Rana Khoury, creative director at Leo Burnett Beirut and lead creative on #Undress522.

“In an ever-changing world, where cruel voices are getting louder year after year, those who do believe in good need to do more to be heard, and campaigning is one the most efficient ways to spread your message.”--Rana Khoury

“One of the agency’s first campaigns, AMAM05, stood against sectarianism, followed by several campaigns supporting women’s rights causes with 'Khede Kasra', ‘No Rights No Women’, numerous campaigns for KAFA, but also against child abuse for Himaya, or 'Bil Alb ya Watan' and many others.

“This strategy is not only a deep belief in the possibility of changing human behaviour through communication, but it is also a strategy driven by management, where our skills are put at the service of good.”

The curse of awards

And then there is work created purely to win awards. Much of this work is done proactively and frequently for obscure charities. And because charities are by definition non-profit organisations, agencies know they will be willing to run advertising that has been created without a brief (with the intention of winning awards), which tends to raise awareness of the agency rather than the charity’s cause. It is this work that gives advertising for good a bad name.

“Much of the language of ‘goodvertising’ is self-congratulatory. ‘We donated’, ‘we helped’, ‘we assisted’. The public easily de-codes these phrases as brands looking for a ‘pat on the back’.”--Paul Barras

“CSR and charity briefs are regarded as award briefs by creative departments,” says Barrass. “They are not subject to the same rigorous scrutiny by marketing departments, who see it as soft and fluffy communication and not about sales figures. This means the creative department has more creative freedom, more latitude to be surprising, thought provoking, shocking or unexpected – which are the qualities awards juries look for… [But] there are many cases where agencies piggyback on humanitarian causes for their own self promotion.”

Nadim Khoury adds: “Every agency has its own views about the issue, but from what we can see, many advertisers and agencies are simply starting to realise the greater value that advertising brings to the table and they have a genuine desire to create good in the community and make a positive change.

“Yes, agencies have to be more creative and focus on associating their ad campaigns with the realities and emotions of their specific target audience in order to achieve their clients’ sales and marketing goals, but they can now do so while making a difference in the world. It’s like, for lack of a better metaphor, hitting two birds with one stone and feeling good about it. It just makes sense. Do more good, and you’ll get it back manifold. Such advertising simply resonates with how the world works in a way. Brands create positive change in the community, and they get rewarded with an increase in mind share, customer loyalty, and sales.”

Problems arise when this desire to do good is not perceived to be genuine. Rather, it comes from a desire for self-advancement instead.

“This is a question of where the motivation comes from,” says Barrass. “When the motivation is intended to bring about good and alleviate suffering or privation, it is life affirming and beneficial to everyone involved. However, when the motivation is to hang on with cadaverous fingertips to the coat tails of war, starvation, and tsunamis for a free ride to the awards podium, it is degrading and corrupting.

“A lot of brands’ messaging in corporate social responsibility gives the impression that ‘I’d like to make an anonymous contribution to your great cause, but just in case you’re interested, here’s my logo’, which is inherently disingenuous. Much of the language of ‘goodvertising’ is self-congratulatory. ‘We donated’, ‘we helped’, ‘we assisted’. The public easily de-codes these phrases as brands looking for a ‘pat on the back’.”

‘Tell me what you’re achieving’

Alex Malouf, chair of the International Association of Business Communicators (IABC) for Europe, the Middle East and North Africa, agrees. “Don’t tell me what you’re spending on others, tell me what you’re achieving for others,” he says. “As a consumer, I really don’t care about how much firm A or B have given to charity (unless it’s my money). What I do want to know is what have you achieved? How many families have you helped? People educated? Diseases prevented?

“As a consumer, I really don’t care about how much firm A or B have given to charity (unless it’s my money). What I do want to know is what have you achieved? How many families have you helped? People educated? Diseases prevented?”—Alex Maalouf

“I should be able to understand the positive impact of a brand, and the causes that it stands for. For example, there’s the Body Shop, which pioneered the sale of cosmetics, which weren’t tested on animals. Then there’s Innocent, the makers of no-sugar added fruit smoothies. There’s not only the cause that the brand stands for, but also the cause that it supports. Take Toms shoes, which donates a pair of shoes to an impoverished child for every pair sold.

“What’s the common thread that runs through these brands? They’re transparent in their charitable goals, they clearly state what has been achieved, and they talk about long-term outcomes. They don’t dangle dollar amounts in front of the consumer in the form of a press release. They don’t talk about the good work their money is doing. Rather, they just get on with the hard work in a transparent fashion.”

There is a clear distinction to be made between advertising for social good and commercially-minded cause-related marketing. The latter largely involves bandwagon-jumping, or trend following, as Kolster recently pointed out in an article for The Drum.

“We need more debates, we need more keynotes, we need more creative solutions embracing sustainable transformation, circular consumption, the sharing economy, new materials, renewables and economic equality.”—Thomas Kolster

“It seems like most agencies and marketers are treating the biggest issues of our time as a new trend, as if doing good is simply the ‘new black’ or perhaps pink (judging from the number of female equality campaigns on show),” he wrote. “Like every brand in the 90s was all about lifestyle, it seems like brands today are firmly on the social issues bandwagon like bees around a honey pot (even though the bees are also a cause we should worry about).”

For Thomas Kolster, the biggest issue – that of over-consumption (which brands are the biggest proponents of) – is not being addressed.

“We need more debates, we need more keynotes, we need more creative solutions embracing sustainable transformation, circular consumption, the sharing economy, new materials, renewables and economic equality,” he said. “Social and environmental entrepreneurs are solving things, while ad land perpetuates more stunts with little to no effect.”

Action, not just words

For any brand to be viewed favourably and not as a cynical bandwagon-jumper only interested in commercial gain, words have to be meant. And they must be followed by clear actions. In other words, substance is a pre-requisite.

“For a social-cause ad to be effective, it has to be genuine and has to sit at the heart of a popular culture,” asserts Nadim Khoury. “Consumers are not naïve. They’re smart and well informed and they can tell the difference between a mere attempt to drive sales or illicit action and a real desire to create positive change.

“What matters is that a social ad campaign brings about the desired change, be it raise awareness about a particular issue, positively shape public perception, or more directly empower and contribute to enhancing the situation and lives of an underprivileged segment in society.

“Advertisers who understand that ‘actions speak louder than words’ and that their ad campaign needs to do more than just raise a culturally-relevant issue have a good chance of achieving results and creating a lasting change. The ones who do succeed go one step further and directly create positive change by offering a real solution to a societal-level issue and – even better – contribute to making it happen.”

However, Kolster believes nowhere near enough of genuine value is being done. He argues that one-offs like the Cannes grand prix-winner ‘Fearless Girl’ for State Street Global Advisors by McCann New York are not creating lasting change. Some campaigns he dismisses as mere gimmicks.

But, as Barrass points out, the honourable motivation to do good can come into conflict with most marketing departments’ view on profit.

“Advertising for good, when it is most effective, has altruism at its core,” he says. “Altruism is sometimes defined as ‘the intentional and voluntary actions that aim to enhance the welfare of other people in the absence of any quid pro quo external rewards’. This is where creative advertising becomes conflicted. ‘The absence of quid pro quo external rewards’ is at odds with the ambitions and instincts of brands and creative departments who crave praise, recognition, profit and reward.”

He adds: “Since the expression ‘modest boasting’ (a statement in which you pretend to be modest but which you are really using as a way of telling people about your achievements) has entered our vocabulary, consumers are suspicious of brands who proclaim to be forces of good, then hit us with their hubristic logos. Consumers’ scepticism and ability to de-code brands’ intentions will dictate how advertising for good will evolve.”

That said, Rana Khoury hopes more brands are realising the importance of their role in making positive change.

“In an ever-changing world, where cruel voices are getting louder year after year, those who do believe in good need to do more to be heard, and campaigning is one the most efficient ways to spread your message,” says Khoury. “The least a great campaign can do is change opinions or the status quo. But it can also go further by changing perceptions and behaviours, or by creating a movement, like ‘No Law No Vote’ for KAFA, or by lobbying for a law, like #Undress522 for Abaad.

“A good idea can influence minds, its implementation can impact behaviours, and its results can lead to change.”

.jpg)

.jpg)