News - Advertising

Japan’s Outdoor Advertising Storm

by Jessie Carpenter

October 16, 2015

.jpg) Advertisement

AdvertisementJames Hollow, President of Lowe Profero Tokyo, a digital-centric agency and the official digital network of Lowe & Partners describes the scene as follows: “Japan’s media and advertising industry is indeed dominated by old-school media in the shape of Dentsu and its old rivals. Their persistent strength is usually put down to the fact that they have long standing exclusive relationships with much of Japan’s biggest media properties, as well as old-boy-network-type relationships with Japan’s biggest ad budget spenders […] advertising that presents and explores an incrementally novel aesthetic will gain notoriety in Japan. In other words, it is not that Japanese culture is shallow, it simply is deep in a different way: aesthetically. Aesthetics for advertising in the broadest sense comprises language (copy), celebrity (talent) [and] design (visual execution).” Hollow believes these unique factors make Japan a challenging place for non-Japanese ad agencies to make headway in the market. And to a visitor to Japan, they make the visuals and approach to outdoor advertising especially foreign.

According to Dentsu, Japan’s overall advertising expenditure in 2014 was 6,152.2 billion yen (to put that in perspective $1 is 119 yen). This is an increase of 2.9 percent over the previous year and is the first time in six years that spending exceeds the six billion mark. Outdoor advertising expenditures increased by 3.3 percent, to ¥317.1 billion. Dentsu partially attributes the rise to higher billboard production costs. The demand for LED signs “is growing” and “poster boards were actively used in a variety of industry categories, including Beverages/Cigarettes, Automobiles/Related Products (especially for imported passenger cars) and Finance/Insurance, as well as in the music, television programming, and movie fields.” There was a solid demand for large-screen displays and “commercial facility media enjoyed a steady flow of placements throughout the year.” This all makes for a rather vibrant outdoor market that is still in full form and shows no sign of waning with the growing prominence of digital advertising.

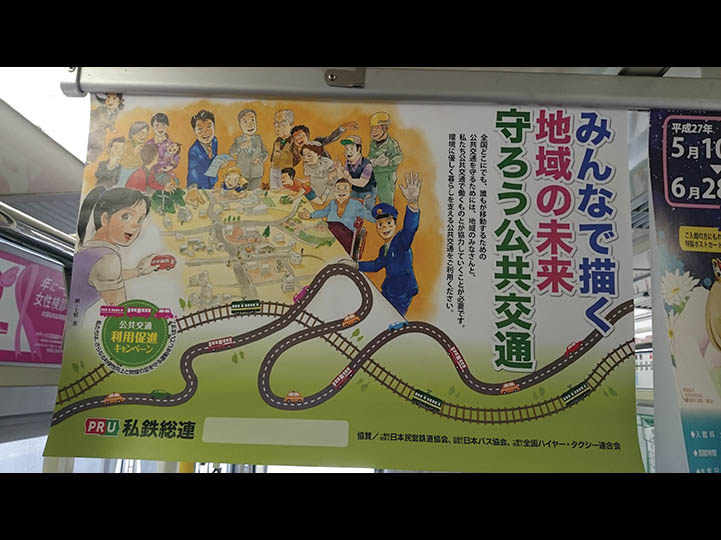

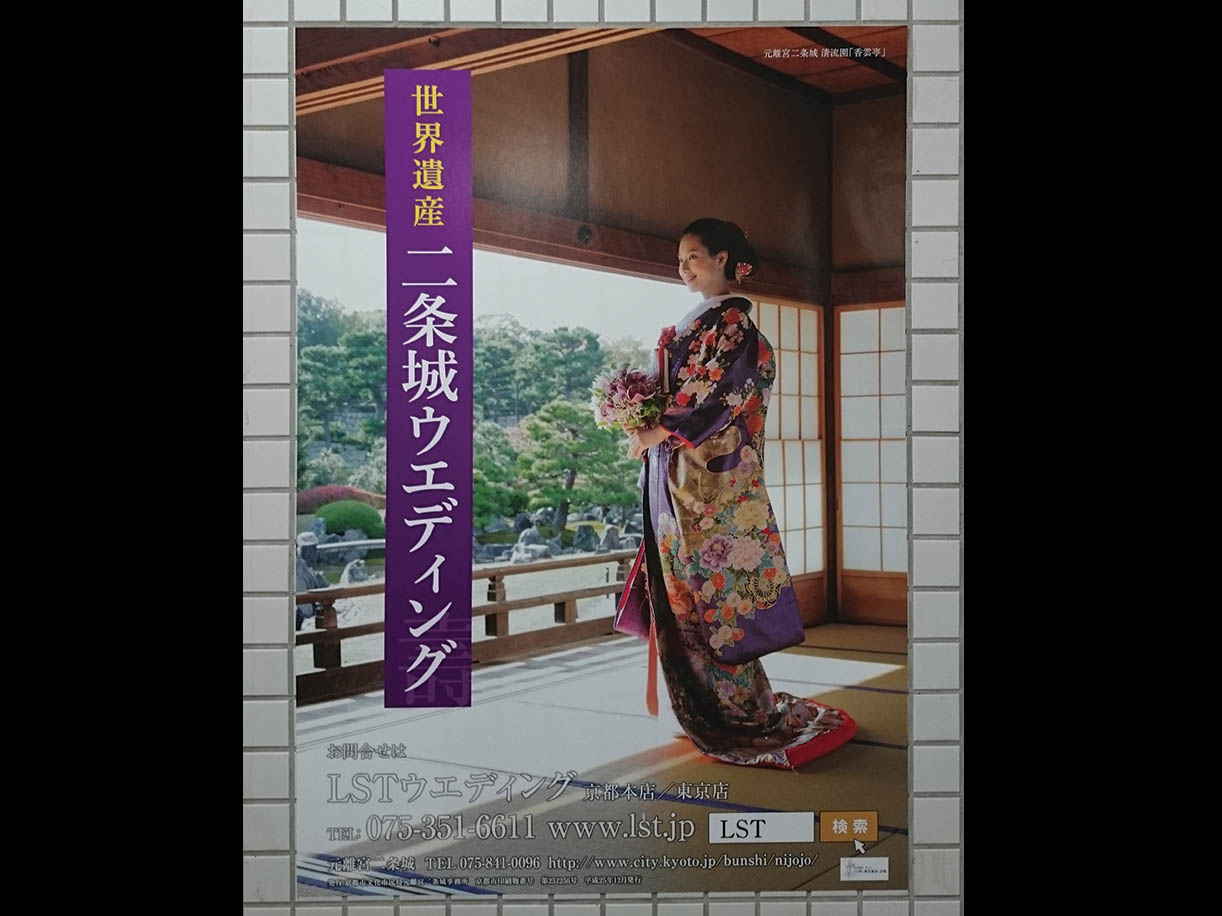

Beyond the flurry of billboards, posters and other forms of outdoor advertising with the images of Japanese celebrities and visuals rooted in Japan’s rich historical and cultural heritage (from women dressed in kimonos to theatrical traditions), one thing is rather striking: the influence of manga and anime on outdoor advertising. Japanese black and white comics (Manga) and Japanese animation (Anime) are extremely popular in the “Land of the Rising Sun” and have succeeded in winning over audiences of all ages throughout the world. Today France and the US have strong fan bases. Many of us raised in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s watched dubbed anime series on TV (while probably not realising they were originally Japanese). The Gulf, KSA, North Africa and the Levant have a growing number of manga and anime enthusiasts. No wonder that the distinctive illustration and animation style is prominent in Japanese advertising.

To best understand the fascination with the style in Japan, it’s important to know a bit about the history. Manga means ‘random pictures’ and the word was first used in the 19th century by a famous ukiyo-e artist (ukiyo-e are mass produced Japanese woodblock prints produced between the 17th and 20th century). Story telling illustrations were not novel in Japan. In fact ‘gi-ga’ (funny pictures) from the 12th century featured many manga traits. The manga we know today emerged after World War Two and is essentially the merger of ukiyo-e and western art. As there are practically no laws that limit what can appear in a manga, artists have total freedom. This is why manga can be very sexual, extremely violent and delved into any topic. This results in manga boasting a wealth of genres and subgenres from action to fantasy and romance. It also has different mangas for different target audiences: shojo (for young girls and teenagers); shojo-ai (love between two female characters); josei (for older women); shounen (for young boys and teenagers); shounen-ai (love between two male characters); seinen (for older men); and more. While manga and anime can feature sex and gore, most don’t. On the contrary, some explore philosophical and existentialist questions, center on very real issues or just provide innocent entertainment.

Oricon’s "Annual Market Report" for book sales in 2014 revealed that the market for compiled manga book volumes rose to 281.51 billion yen (about $2.3792 billion). That just shows how massive the attraction of manga is in Japan alone. This has given rise to firms like Ad-Manga.com specialised in translating advertising concepts into illustrated manga renditions for print and web. This has also had an obvious impact on outdoor advertising.

The impact of manga and anime manifests itself on several levels. Images from well-known old anime series are used. Characters from popular new anime and manga are common. The iconic illustration style is used for public awareness ads such as ones that encourage trendy teens to use the metro and ones that encourage them to protect their password. The unique fashions found in manga has trickled its way to the mainstream and is showcased in the outdoor advertising of big brands such as Shiseido. Firms have created their own mascots in the recognisable style. Shops even have people dressed up like manga characters outside to encourage people to step inside.

The influence of manga and anime are so entrenched in the culture that well-known characters like Hello Kitty are everywhere. Even sweets come in special manga packaging. And the influence is not limited to Japan. For instance in 2013 L’Oreal released a mascara called ‘Miss Manga’, which is supposed to make your eyes standout like the eyes of a manga character. Manga and anime have even infiltrated advertising abroad with examples including animated ads for Murphy’s Irish Stout dating back to 1997.

In a nutshell, the overall outdoor advertising experience is very different from the Middle East. The overwhelming abundance, sense of aesthetic and preferences of the audience lay the foundations for advertising that is very culturally specific. While “culturally shallow” design that can be found everywhere and anywhere exists in Japan, a lot of the outdoor advertising is “culturally deep” and hence can’t be "copied and pasted" in any other country without substantial adaptation. Could this be part of the reason why spending is still going strong and can the MENA region learn anything from this?

.jpg)

.jpg)