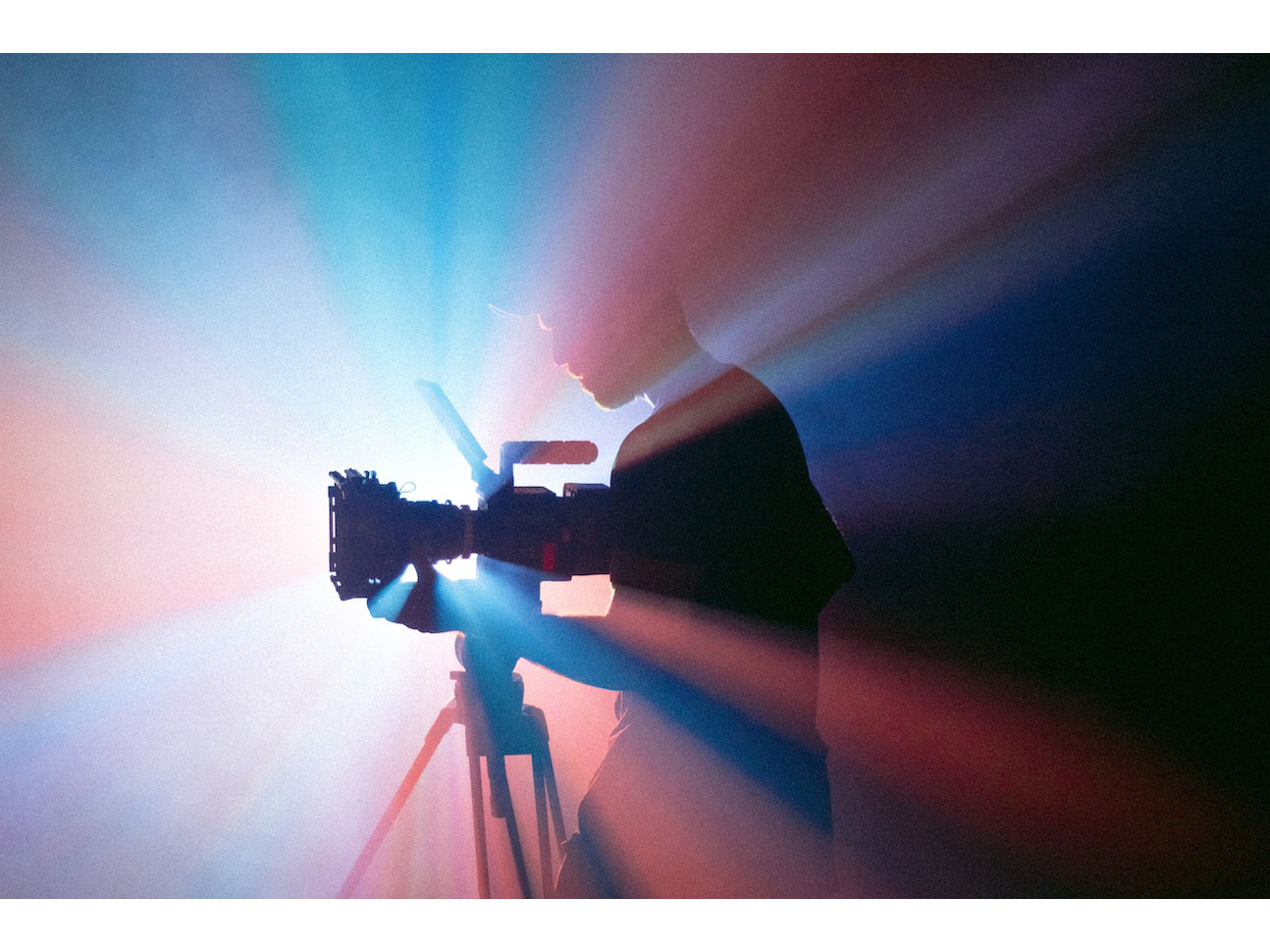

Industry Talk

The last picture show? On Lebanon’s film and production sector

by Iain Akerman

February 20, 2023

.jpg) Advertisement

AdvertisementIf you want to know what it takes to bring a production industry to its knees, ask the Lebanese. The political, economic and pandemic-related crises that have consumed the country have almost destroyed one of the region’s greatest assets – Lebanon’s film and production sector.

As Paul Sabbagh, the managing director of Wonderful Productions, notes, the country’s successive crises initially led to a total paralysis of production. This was followed by the migration of talent and many of the companies that employed them. Just like their counterparts in the advertising industry, many production houses have sought sanctuary abroad, particularly in the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

Wonderful Productions, for example, took the decision to shift its head office to Dubai and invest in a new operation in Saudi Arabia. The move meant the company could continue to cater to its regional clients. It also ventured into Eastern Europe as a backup. Clandestino opened an office in the UAE and consolidated its presence with local partners in Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Egypt. The Talkies launched an office in Riyadh to better address the needs of the Saudi market and took the decision to reduce or relocate team members. EFX Films launched an office in Saudi Arabia and tried to maintain its staffing levels by pushing its presence in the Gulf and diversifying its product deliveries.

“I think what the crisis did is pretty obvious, in that it forced a massive amount of talent out of the country looking for stability and opportunities elsewhere,” says the screenwriter, director and visual artist Areej Mahmoud. He himself moved to Dubai in 2019 and co-founded Studio Humbaba, a story development company, the following year.

“Producers and filmmakers are still keeping the industry going in Lebanon.”--Areej Mahmoud

Following the port explosion, Big Kahuna Films offered its team the option to relocate to Dubai. Although that placed strain on the Dubai office’s finances and lightened the Beirut operation, the well-being of the company’s team was of paramount importance, says Eddy Rizk, the company’s chief executive. “For us, producing in Lebanon was always for the region, while offering very competitive rates and a well-developed industry,” he says. “So if we are talking about the economic crisis, that alone wouldn’t have affected us that much. However, the geopolitical fiasco of the Lebanese government, plus the latest security concerns, made Lebanon a country where clients became hesitant – and were sometimes even banned – to go. This made most of the production industry professionals relocate to other countries. And the biggest asset in our industry are the people.”

“Unfortunately for Lebanon, our strategy is to strengthen our presence abroad.”--Paul Sabbagh, Wonderful Productions

Others, including City Films, stopped working for the Lebanese market years ago, but some stubbornly remain and refuse to open offices abroad. Amongst them is Ginger Beirut Productions, which is run by Abla Khoury and Lara Karam Chekerdjian. “Not opening an office outside of Lebanon was a decision that Abla and I took together,” explains Chekerdjian. “We wanted to stay, we wanted to fight our own fight, so we chose to stay here and try to keep shooting and doing the things we do.” Their work has shifted over the course of the past few years, with a move towards documentaries and series about Lebanon, the revolution and the country’s economic and political crisis.

“The exodus of talent from Lebanon did not halt the local production industry,” says Mahmoud. “Producers and filmmakers are still keeping the industry going in Lebanon. It’s actually quite impressive that they can keep going despite the total collapse. I still source work to Lebanon, be it in grading, music composition, sound design and post production. Despite it all, we still have some exceptional talent based out of Lebanon. I know there are several series and films being developed and shot in Lebanon as well. I shot my short film last summer in Beirut, and besides the logistical challenges, the quality of production was as good as ever. Production in Lebanon still benefits from expertise and informal systems of organisation and collaboration that were able to adapt quickly to the collapse.”

That said, the quantity of work being produced in the country is significantly down. Although estimates of how many commercials, videos or feature films are being produced in the country are hard to come by, you get a sense of the scale of the drop from the production houses themselves. The Talkies says its volume of work in Lebanon has decreased by 60 per cent compared with 2019. Clandestino provides a similar figure of 50 to 60 per cent. “We used to cater for lots of shoots for the banking sector and the telecoms sector, both have been silent since [the crisis] and no demand for any communication was asked for,” explains Ray Barakat, managing executive producer and partner at Clandestino. “Also, we used to cater for a lot of FMCG clients in Lebanon. Even though household consumption kept on being spent, clients were reluctant to spend anything on communication and production. Add to the above the political regional turmoil, which also affected us and led many regional clients to not come to Lebanon for shoots anymore.”

“From being the most creative and quality driven market, Lebanon is now in survival mode.”--Gabriel Chamoun, The Talkies

In an attempt to attract work, production houses have tried different strategies. Barakat says he has encouraged all suppliers and freelancers to lower their costs and has attempted to ensure that some clients still shoot in Lebanon. Clandestino also diversified its work in terms of genres and markets, catering for the region and, in some cases, for production services coming from Europe. EFX Films reduced its costs, says Eli Srour, the company’s owner and chief executive, and has sought to create more diversified solutions in the production industry, while simultaneously expanding its presence in Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Oman.

“As with all other industries, we have been severely hit,” admits Gabriel Chamoun, chief executive of The Talkies. “One would think that local currency devaluation would help exports of goods and services. However, in our case, it came in parallel with many other factors such as the Covid situation, local political and security issues, and the pressure from Saudi public and private sectors to localise TV commercial production. Hence, the decrease in production costs didn’t attract more business to Lebanon.” The end result is less and less high quality TV commercials being produced locally, says Chamoun. “From being the most creative and quality driven market, Lebanon is now in survival mode.”

“The whole region is like one big studio, where you can start a project in Dubai, film a part in Beirut and finish it in Riyadh.”--Eddy Rizk, Big Kahuna

What work is being carried out in Lebanon faces its own series of challenges. The migration of talent has led to a shortage of professional crew, while the availability of ‘fresh’ dollars is an ongoing concern, says Srour. “Whenever we need to produce locally we have a problem finding the right talent, whether the director or the rest of the production team,” admits Sabbagh. In addition, undercutting is rife, with crews and equipment providers facing competition from an unregulated element within the market. All of which is on top of the destabilising and unpredictable political environment, which has led many regional clients to place Lebanon on a red list for their employees.

“I think it’s a survival mode at this point,” says Khoury. “You don’t know what could happen tomorrow. Usually you put in place a strategy and you say ‘this year I’m going to do this, this and that’. Now we don’t know what will happen next week. We have a shoot in one week and we’re thinking, ‘do you think it’s going to happen?’ The situation is very unstable.” Chekerdjian agrees: “One day they close a road, one day they open a road, one day you can have a permit, the second day the guy is not there so you don’t have your permit. It’s more difficult than usual.” Arguably more concerning, however, is a noticeable change in mindset. “Usually we have a script and a director, we start calling the crew, we say we have an amazing script, we have a good director, they have a vision,” says Khoury. “Now people – crew wise – don’t really care about all this. They need money to pay the bills, so there’s even something in the core of the passion of cinema people and the new generation that has shifted.”

All of which is understandable given the circumstances. Lebanon is now classified as a lower-middle income country by the World Bank and is in the midst of one of the world’s worst economic crises since the middle of the 19th century. “It remains unfortunate that the talented people in Lebanon who have contributed to a thriving production scene over the years are just surviving, and not thriving,” says Mahmoud. “The region is going through a major change. Streamers compete for content and regional content is in high demand, but in Lebanon we are at a disadvantage. Lebanon is a less attractive market for streamers because it is a small market compared to the region. Not to mention that very few people in Lebanon still own a functioning credit card to subscribe to any streaming service at all. And so as Lebanon becomes a less attractive market for streamers, I worry that production in Lebanon will focus on servicing, and we will be less capable of finding funding to tell our own stories.”

“In the end we will prevail and adapt and innovate like we have been doing.”--Elie Srour, EFX Films

The overwhelming response to this reality will be a continued focus on markets outside of Lebanon in 2023, while making the most of the country’s talent – wherever it may be. “Unfortunately for Lebanon, our strategy is to strengthen our presence abroad,” admits Sabbagh. The Talkies, too, will seek to consolidate its footprint across the GCC and Egypt. It also plans to develop “compelling regional and international projects in TV and film”. Clandestino is looking at further diversification and will attempt to break through with longer format ventures, says Barakat. As for Big Kahuna Films, it will keep its finger on the pulse in Lebanon while concentrating on the wider region and possibly further afield.

So what about Lebanon? Is there hope for production in the country? Barakat believes so, although trust has to be rebuilt. Without it, the country will continue to stagnate. “Build that trust again and create more incentives for [clients] to come back to Lebanon,” he says. How? “By keeping competitive prices compared with the region and promoting the benefits of shooting in Lebanon: great weather, easy to manage production flow and [the ease of obtaining] permits, abundant versatile locations, great nightlife and food.”

Sabbagh agrees. “Despite all the challenges, I still believe that Lebanon has all the ingredients to get back a big chunk of the business in the region,” he says. “We have the greatest quantity of talent in this industry in the region, the highest variety of actors you can find locally, the best weather all year long, and travel and accommodation are still the most competitive. The bottom line is we can still offer the best quality/price ratio. However, nothing can happen if the country doesn’t help us restore confidence.”

And therein lies the crux of Lebanon’s predicament. If the country’s political and economic crisis continues, nothing will change. “I don’t want to sound negative, but there won’t be any improvement until there are major political reforms,” states Chamoun. “Unfortunately, the main challenge is not industry related. It has to do with the failed state Lebanon has become at all levels – judiciary, social, energy, security etc. Brand Lebanon has been built over the past century by a dynamic private sector, an educated workforce with a can-do attitude, talent, sophistication and taste. They have managed to ruin everything.”

Chamoun is far from alone in this belief. Sabbagh goes as far as saying nothing can be done, apart from maintaining ‘good and trustworthy’ relations with countries such as the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Then at least Lebanon will remain part of the region’s production ecosystem, even if its role is severely diminished.

“There’s even something in the core of the passion of cinema people and the new generation that has shifted.”--Abla Khoury, Ginger Productions

The old Lebanese resilience is still there, of course, although strangely subdued. “We have been in the industry more than 25 years and we have been facing challenges all our life,” says Srour, who believes the local market’s shrinking budgets have to be capped. “In the end we will prevail and adapt and innovate like we have been doing.” Srour also believes that the importance of video in clients’ content marketing plans has to be pushed, while advocating Lebanon as a hub for advertising and film production. The latter is arguably a pipe dream, but if anything’s going to succeed it’s going to be the experience, creativity and innovation of the Lebanese people.

“It will take a long time to rebuild trust,” believes Rizk. “We will need to feel confident again to invest money and time and to invest in people. What keeps this country on its feet are Lebanese people living abroad, so if we can afford it, even if it eats up our profit, we will never close our Beirut operation and will use the first opportunity to build the industry again, in one way or another.

“Saudi is on the rise and Dubai is of an international level,” he adds. “The whole region is like one big studio, where you can start a project in Dubai, film a part in Beirut and finish it in Riyadh. Exchanging resources, talent, crew, and even equipment. And this is how the industry in the region will continue to evolve. A strong percentage of the regional industry workforce is Lebanese. And only as a part of this interconnected regionally growing market will the production industry in Lebanon survive.”

.jpg)