News - Advertising

Israel-Gaza: Brands, Boycotts and Blowback

by Iain Akerman

November 13, 2023

The day after Hamas’ attack on Israel, the US clothing company American Eagle updated its flagship billboard in New York’s Times Square. Replacing its usual advertising with an image of the Israeli flag, the brand announced that it stood firmly in solidarity with Israel. For some, it was a much needed message of support. For others, it was confirmation of the company’s complicity in the ethnic cleansing of Palestine.

The billboard was brought to the world’s attention by Craig Brommers, American Eagle’s chief marketing officer. A short post by him on LinkedIn, accompanied by an image of the billboard, stated simply: “Our updated American Eagle Times Square flagship billboard.”

Messages of thanks flooded in, but so too did messages of dissent, with many lamenting the company’s solidarity with a country that Amnesty International has accused of “committing the crime of apartheid against Palestinians”. Brommers’ post has since been removed. In response to an interview request via LinkedIn, his public profile was disabled.

Perhaps unlike any other, the Israel-Hamas war has highlighted the dangers of brands becoming involved in international affairs. Aside from the ethical issue of businesses taking sides in a conflict, the fallout can be disastrous, even for those companies that have previously engaged in brand activism. From reputational damage to plummeting sales, the risks can be pronounced and potentially enduring.

“I believe that it is not in the gift of a brand or business to take sides in an international conflict,” says Asad ur Rehman, chief executive of So&So Partnerships. “Firstly, regardless of which side of the conflict a business stands on, their political stance is sure to come across as more opportunistic than sincere or right. Additionally, there are some very obvious risks that arise out of such stances.” These risks include the potential for consumer fallout, as well as the danger of being targeted by “political groups or governments, possibly leading to sanctions, bans, or other forms of economic retaliation”.

“Political situations are inherently volatile. A brand’s association with a particular side may backfire if the political winds shift or if the conflict escalates or resolves in an unexpected way.”

--Asad ur Rahman, CEO So&So Partnerships

Consumer fallout is already a reality in the Arab world. Calls to boycott brands such as McDonald’s, Burger King, Carrefour and Domino’s Pizza have gathered momentum as Israel’s attack on Gaza has intensified. Branches of McDonald’s and Starbucks have been attacked in Lebanon; outlets of Western brands have closed their doors in Qatar; and billboards in Kuwait have asked: ‘Did you kill a Palestinian today?’ The latter targeted consumers who continue to buy from brands that support Israel.

Where do these boycotts stem from? For McDonald’s, from a decision by the fast food giant’s Israeli franchise to give thousands of free meals to Israel Defence Forces (IDF) personnel. TikTok videos of IDF soldiers enjoying a quarter pounder with cheese and a side order of onion rings as bombs rained down on Gaza have not been well received. Nor has Carrefour’s association with illegal Israeli settlements in the West Bank through its partnership with Electra Consumer Products and its subsidiary Yenot Bitan.

In a bid to limit the damage, McDonald’s issued a statement on some of the social media channels of its regional franchises, including those in Bahrain, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. “McDonald’s Corporation is not funding or supporting any governments involved in this conflict, and any actions from our local development licensee business partners were made independently without McDonald’s consent or approval,” said the statement. “Our hearts are with all of the communities and families impacted by this crisis.” But it was too late. The damage had already been done.

“Palestinians have lived under the oppression of occupation for far too long,” says Dalia Abuzeid, a Dubai-based Palestinian film producer. “They have been killed, injured, and displaced. They’ve had their land stolen, their culture stolen, their future stolen. They have been brutalised and murdered. And yet governments from across the world continue to support Israeli violence and aggression. So, too, do brands such as McDonald’s and Starbucks, who support this genocide against the Palestinian people.

“I’ve never seen brands support genocide before. I haven’t seen brands support the oppressor in the war on Ukraine. So hitting them hard economically is important. Because we have realised that the governments of the world – especially those who claim the moral high ground with regards to human rights and international law – are supporting Israel and their ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians. The least we can do is try to hit them in another way. And that way is economic.”

“Ultimately, brands are vessels, and those vessels are steered by people. People are partisan, emotionally involved and may be influenced by a whole raft of intertwined factors.”

--Kamal Dimachkie, COO Toughlove Advisors

How big an impact this boycott will have is a matter of conjecture. “The immediate and adverse consumer reactions will hurt the businesses in the short term in the region,” believes Rehman. “Depending on the outcome and resolution of the current state of affairs, this impact could last longer too.”

Others are unsure, believing boycotts have little impact on a company’s bottom line. However, you only have to look at the BDS (Boycott, Divestments and Sanctions) movement, which is considered an existential threat to Israel, to know that boycotts work. The BDS movement, as with most other forms of resistance against Israel, has been deemed antisemitic by the Israeli government and pro-Israel groups.

“It is going to be very interesting to see the overall reaction from our wide region, how unanimous it will be, and how deep it will manifest itself,” says Kamal Dimachkie, partner and chief operating officer at Toughlove Advisors, a Dubai-based business consultancy. “Judging by the reaction to events and the news, one would expect a uniform reaction and response, but to what extent people vote with their feet and wallets is yet to be seen.

“Overall, one would expect reputational blowback, calls for boycott and even some level of boycott which will result in potentially lower sales. Let’s not forget that the unfolding events touch a deep and a long-exposed raw nerve and, historically, Arab audiences have not been shy of expressing strong views towards brands that were seen to have crossed the line.

“The above said, I am mindful of the Arab employees and stakeholders of such global brands in our region. We shouldn’t forget that those brands bring food to the table for many a family in our region, especially as many global brands have established a strong foothold locally and have been adopted by the region.”

There are, however, perhaps more damaging issues at play. One of the risks of taking a political stance is disagreement among employees, says Rehman. That stance can “create divisiveness within the company, potentially affecting employee morale and productivity if staff members have differing views.” Nowhere has this been better exemplified than with Deloitte and Google, both of which have experienced internal dissent.

When the professional services network posted a message from the Deloitte Israel team on LinkedIn, that message was one of support for Israel. “During these challenging times, we wholeheartedly support both our fellow citizens on the home front and those on the front lines,” ran the post. “Our prayers are fervently directed towards the swift recovery of the wounded and the safe return of the abducted.” There was no mention of the suffering in Gaza. Nor has there been since. As one reposter noted: “I don’t remember ever seeing Deloitte post once in the last decade in support of the Palestinians.”

Significantly, a number of employees sought to publicly distance themselves from the message. Lara Kesserwan, a business analyst at Deloitte, reposted the message, noting that: “This post doesn’t represent me as a Deloitter. I stand with justice and humanity. I stand with Palestine.”

Faris Ahmad, a consultant for the company, also stated his objections: “As an employee of Deloitte, I want to make it unequivocally clear that this post does not align with my unwavering support for my country, Palestine, and our ongoing struggle for justice and peace. I am deeply committed to advocating for the rights and well-being of my country.”

Deloitte is by no means alone. The US-based database management company Oracle, which has offices across the Middle East, posted on LinkedIn that it “will provide all support necessary to the Government of Israel and defense establishment”. Google and Microsoft, both of which have a sizeable presence in the Gulf, have also issued messages of support for Israel. Meanwhile, employees that have stood in solidarity with Palestine, including those at Google and Meta, have faced hostility and recrimination.

In an open letter posted on Medium, Google workers condemned the company’s “internal culture of hate, abuse, and retaliation”. They also called for Google’s leadership to immediately “issue a public condemnation of the ongoing genocide in the strongest possible terms” and for the company to end its involvement with Project Nimbus. That project involves the supplying of Israel and its military with artificial intelligence and cloud computing services.

“We are Muslim, Palestinian, and Arab Google employees joined by anti-Zionist Jewish colleagues,” said the workers’ joint statement. “We cannot remain silent in the face of the hate, abuse, and retaliation that we are being subjected to in the workplace in this moment. As we mourn the continued and relentless loss of innocent Palestinian lives, including those of our own loved ones, our collective grief is exacerbated by campaigns of hate, abuse and retaliation inside Google. Palestinians have been publicly called ‘animals’ on official Google work platforms, as leadership has stood idly by. Muslims have endured accusations of supporting terrorism as part of their religion and associated slander against the Prophet Muhammad – again, as leadership has stood idly by.”

The repercussions are likely to be long-lasting. Google, Deloitte and all other companies that have either supported Israel or censured, silenced or fired their employees are now at risk of long-term reputational damage in the Arab world. The question is to what extent. As Rehman notes, a “political stance can fundamentally alter the brand’s image, sometimes irreversibly, and not always in alignment with the company’s long-term branding strategy”.

“Taking side, irrespective of the motivations, runs the risk of squandering capital and losing customer base,” adds Dimachkie. “Independent of its size, the economic impact will always be much smaller than the reputational impact and the emotional scars such a position might generate. We need to remember that while time heals all wounds (ultimately), the affronted will remember how they have been made to feel for quite some time to come, and if in doubt just check what Danish brands are still struggling with in the GCC and specifically Saudi Arabia.” Dimachkie is referring to the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten, which printed a cartoon of the Prophet Muhammad in 2005, triggering a regional boycott that lingers today.

With all this blowback, why do brands get involved? It’s not as if they wouldn’t have known of the potential consequences. Coca-Cola’s reputation in the Arab world is still tarnished, despite the roots of its boycott stretching back to the Six-Day War in 1967.

Indeed, the boycott of brands that openly support Israel or condone its occupation of Palestine has a long and creative history, so why have brands with no traditional affiliation with Israel taken a stance?

The answer lies partly in the scale and nature of Hamas’ attack on 7 October, which led to the killing of an estimated 1,200 Israelis. The limited size of a brand’s presence in the Middle East may also mean any damage is negligible. But there are other factors at play.

“Ultimately, brands are vessels, and those vessels are steered by people,” explains Dimachkie. “People are partisan, emotionally involved and may be influenced by a whole raft of intertwined factors.” These include alignment with a brand’s values and beliefs; pressure from employees and customers; and consideration of how a brand’s actions will be perceived by the public. “Even though brands are not principal actors in global events, they don’t wish to become the story in them wrongly sitting on the fence,” adds Dimachkie. The personal values and beliefs of a company’s leadership can also play a significant role.

Certainly a number of global CEOs have made a point of expressing solidarity with Israel. When Ola Kaellenius, the chief executive of Mercedes-Benz, announced that the German automotive company would be donating €1 million to United Hatzalah, an aid organisation dedicated to saving the lives of Israelis, and the German Red Cross, no mention was made of Gaza. Stating that the safety of the brand’s staff in Tel Aviv was of “the utmost priority”, Kaellenius wrote that his thoughts were with “the many injured, those kidnapped and their families”. No statement of support for the Palestinians has followed, despite the fact that 11,078 Gazans had been killed at the time of writing. Of those killed, 4,506 were children. A further 26,457 Palestinians have been injured, according to Gaza’s health ministry. These figures do not include the 178 Palestinians killed in the West Bank since 7 October. At least 1.5 million Gazans have also been displaced and forced to move to the south of the enclave.

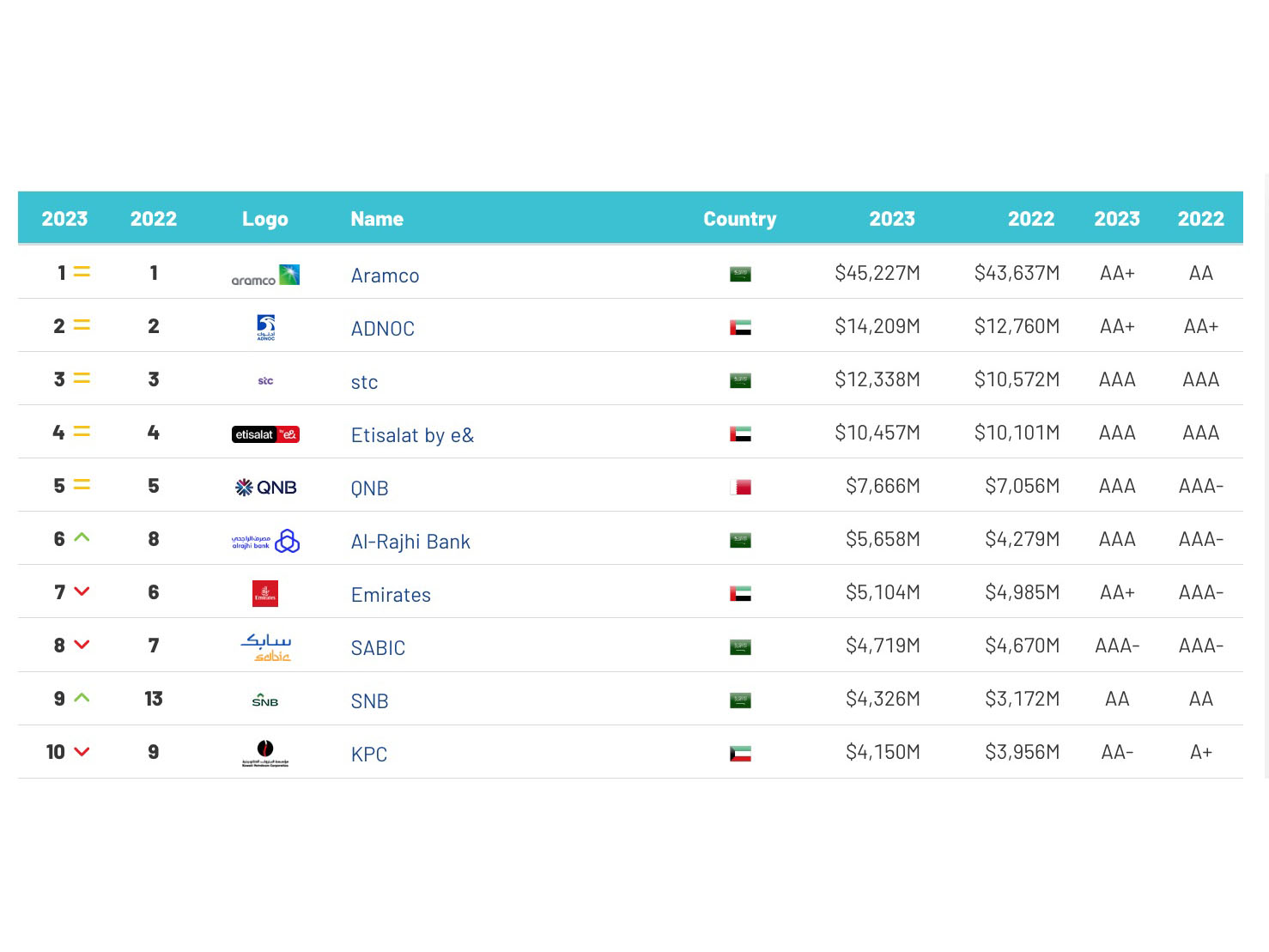

The Yale School of Management’s Chief Executive Leadership Institute has compiled a list of those companies that have condemned Hamas’ attack and expressed solidarity with Israel. Updated in real time by Professor Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, the list includes brands such as Adidas, Apple, Amazon, Boeing, Disney, IBM, Mastercard, Netflix, Pfizer, Siemens, Volkswagen, and Zoom. A corresponding list of those companies that have condemned Israeli aggression on Gaza and the West Bank does not exist. Neither does a list naming those that have called for a ceasefire. Sonnenfeld did not respond to a request for comment.

All of which underlines the universal silence that has greeted the humanitarian disaster in Gaza and the erasure of Palestinian suffering. Only those brands with Palestinian heritage, or those based in the Arab world, have spoken out. This is unlikely to change, even though some companies have stressed the importance of alleviating the suffering on both sides.

The winds of war, however, are fickle. Brands that once stood firmly with Israel may become increasingly nervous as the world bears witness to the unfolding catastrophe in Gaza. This nervousness can reveal itself in many ways – the removal or editing of posts (see American Eagle); the sudden refusal to comment; and a pivoting to concern for universal human values. Although not speaking about the Israel-Hamas war, such a shift highlights what Rehman describes as the ‘aftermath risk’. “Political situations are inherently volatile,” he says. “A brand’s association with a particular side may backfire if the political winds shift or if the conflict escalates or resolves in an unexpected way.”

The political winds are shifting, with increased calls for a ceasefire (driven by public protests and NGOs), even from countries such as France. What remains, however, is the question of why so few companies stand in solidarity with the oppressed. Brands that have been quick to speak out on socio-political issues in the past have remained silent in the face of Israel’s assault on Gaza. They have spoken out in solidarity with Black Lives Matter and campaigned for LGBTQ+ rights, so why not Palestine? Why do so few take the side of the oppressed?

The answer is multifaceted, believes Dimachkie. “From a strong profit motive to perceived risk; from fear of controversy and getting bogged down in a morass that brands prefer to stray away from; from a lack of understanding of the issue and a lack of empathy to those oppressed to the total absence of a developed social-justice agenda. These are some of the reasons that come to mind,” he says.

“Times are a changing,” he adds. “There was a time when brands were not really expected to play a social role, and if they were there was no developed agenda and a playbook that defined a brand’s position, along with the behaviour that accompanied that position. However, today, we are noticing more and more brands are wading into social issues, though their respective positions tend to reflect those of the communities and cultures from which they hail. Clearly there is a shift in societal expectations, and I expect that we are living defining times whose outcome may well bring about a shift in how brands interact with global events. Whatever the shift, whatever the expression, it will always reflect the people who steer them.”

.jpg)